Nazi Forced Labor – Background Information

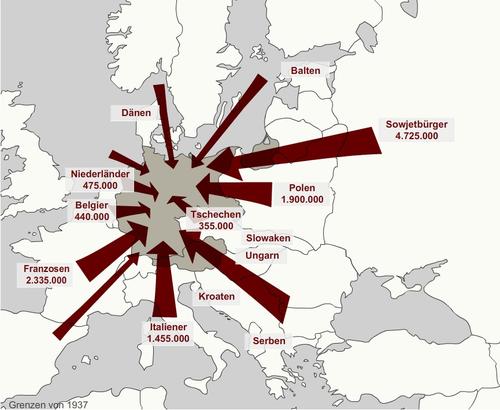

Countries of Origin

Image Credit: CeDiS / FUB click to open

Nazi Germany created one of the largest forced labor systems in history: Over twenty million foreign civilian workers, concentration camp prisoners and prisoners of war from all of the occupied countries were required to perform forced labor in Germany in the course of the Second World War.

At the height of the so-called “Ausländereinsatz” (use of foreigners) in August 1944, six million civilians were forced to perform forced labor in the German Reich, most of them from Poland and the Soviet Union. Over one third were women, some of whom were abducted together with their children or gave birth to their children in the camps. In 1944, nearly two million prisoners of war were exploited to work in the German economy. From 1943, German industry also increasingly used concentration camp detainees as a source of forced labor.

Forced Labor in the War Economy

All of the countries invaded were used to serve as labor pools for Germany. Initial recruitment attempts were with little success; after Czechoslovakia and Poland more and more men and women from Western Europe were also conscripted – sometimes all persons of a certain age group. However, following the failure of the “Blitzkrieg strategy”, the year 1942 brought about a substantial turning point as the German Reich converts to a “total war” economy. In the face of having drafted nearly all German male citizens, this could only be realized by the mass exploitation of foreign labor. They constituted over one fourth and in some factories up to 60 % of the workforce in some departments. Only with them could the population be sustained with supplies and the arms production, organized by Albert Speer as Reich Minister of Armaments, maintained. Major corporations as well as small craft industries, communes and administrative offices, but even farmers and private households continued to demand more and more foreign laborers and, in this way, they were jointly responsible for the system of forced labor. The industry profited from the expansion of production made possible by forced labor.

The Forced Laborers' Living Conditions

The living conditions of the people required to perform forced labor in Germany or in the occupied territories varied from nation to nation and according to legal status and gender. People from the Soviet Union (in the jargon of the Nazis, so-called “OST-Arbeiter” or Eastern workers) and from Poland were defenselessly subjected to the discriminatory special orders of the arbitrary nature of the Gestapo and other policing departments. Often, they were only allowed to leave their camps to work and were required to wear a badge with the corresponding designation (“OST”, “P”) on their clothes at all times. This racial hierarchy of the Nazi regime was supported by the widespread anti-Slavism among the German people, which led to additional insults, denunciations and mistreatment. As alleged traitors, the “military internees” abducted and taken to Germany after Italy’s surrender in the autumn of 1943 also were miserably treated. Life for the skilled workers and engineers attributed to Western Europe or the “Nordic race” were more bearable, but nevertheless characterized by deprivation and humiliation. What was endured by the concentration camp prisoners, particularly Jews, Sinti and Roma targeted for “Vernichtung durch Arbeit” (extermination through labor) was slave labor at its worst.

A System of Racist-bureaucratic Repression and Control

All foreign laborers were subjected to constant surveillance by the racist bureaucratic repression and policing apparatus of the Wehrmacht, labor office, Werkschutz (plant police), SS and Gestapo. They were squeezed into drafty barracks or overcrowded guesthouses and banquet halls. Supplied with completely inadequate rations in the camp and factory canteens and without food stamps to buy food with their meager wage, they were constantly suffering from hunger. They were even more defenseless than the German population in the face of air raids since most of them had no access to shelters. Many women suffered additional harassment and violence. Despite repression, denunciation, loss of orientation and the devastating living conditions in their occupied and plundered homeland, forced laborers repeatedly tried to flee; there were also resistance and sabotage attempts. Without legal means of appeal, even the mere suspicion of these offenses could result, in extreme cases, in deportation to concentration camps or even execution. In cases of “idling” or refusal to work, there was the threat of the infamous “work education camps”.

After the Liberation

After their liberation, many former slave laborers immediately started back for home on their own; others continued living in camps as displaced persons waiting for their repatriation or departure to the West. For many, particularly for Soviet forced laborers, 1945 was not yet the end of their suffering. At home, they were suspected across the board of collaboration with the Germans; many disappeared in Stalinist camps. Most of the survivors, especially those in old age, still suffered from the psychological and physical consequences of the “Totaleinsatz” (total appointment order); they have been living in poverty in many Eastern European countries since the collapse of the socialist societies. The German governments and the businesses that profited from the slave labor system have denied – with very few exceptions – any kind of acceptance of responsibility for these victims.

Further Information

- Information Portal of the Bundesarchiv: www.zwangsarbeit-eu.

- Links: List of Links